Picture this: the top team of an organisation gathers for an emergency meeting. During this meeting, a small group of executives tries to impose their own agenda on the rest.

The meeting turns into what we call a ‘love fest’, where executives positively express themselves about the upcoming changes. All good, right? Wrong. Because hours later, the real opinions are uncovered at the coffee corner. Alternatively, the boardroom becomes a ‘war zone’, where cliques of colleagues are sticking together, no matter the topic.

Now imagine the effect of this type of leadership on the rest of the organisation.

Exhausted employees share stories of frustration, while anxiously ‘checking as many boxes’ as possible before the end of the day (or not). Meanwhile, more and more customers move their business to an industry disrupter because of their ‘innovative approach’.

Sounds like a gloomy scenario, doesn’t it? Still, this is the harsh reality of what happens in some organisations every day.

The most dangerous ‘organisational energy’ drainers

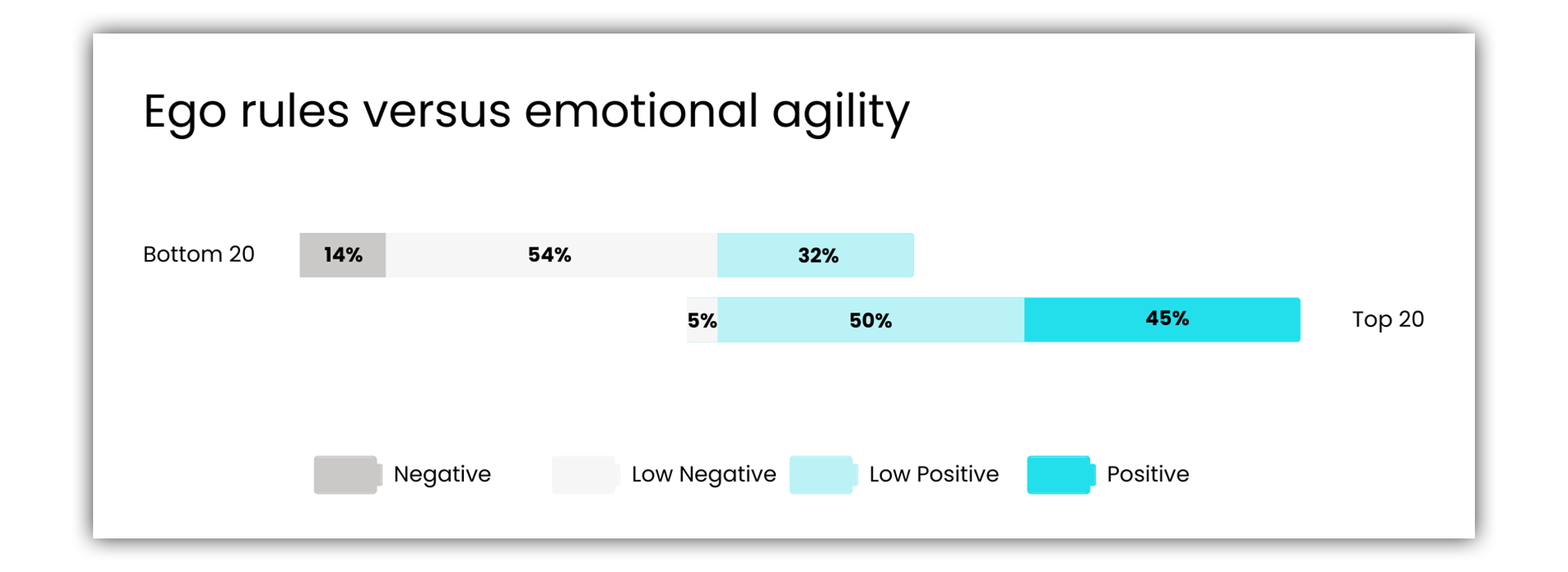

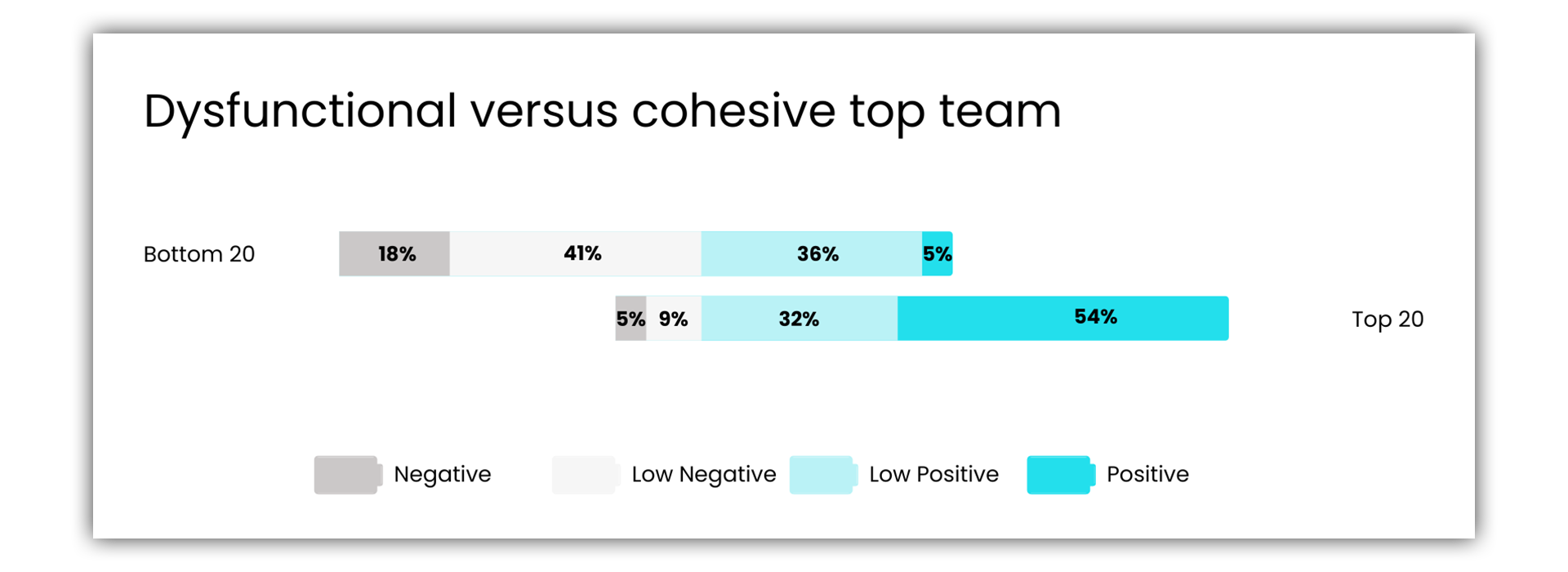

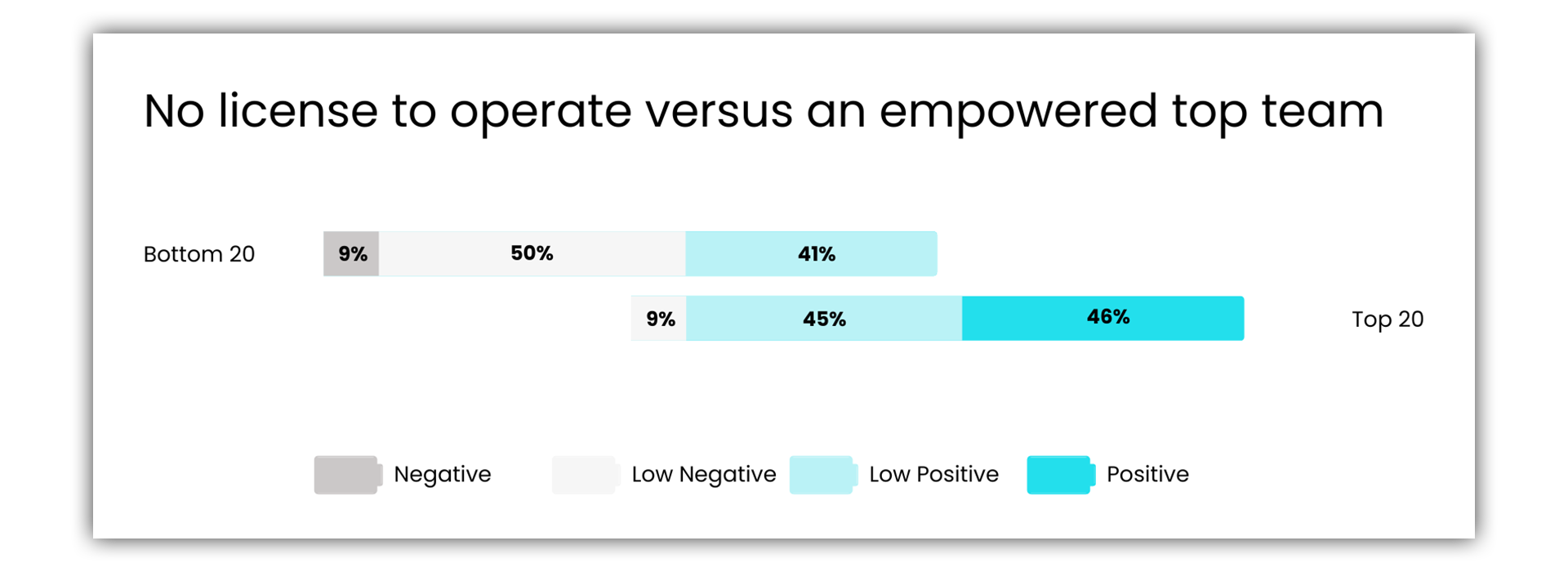

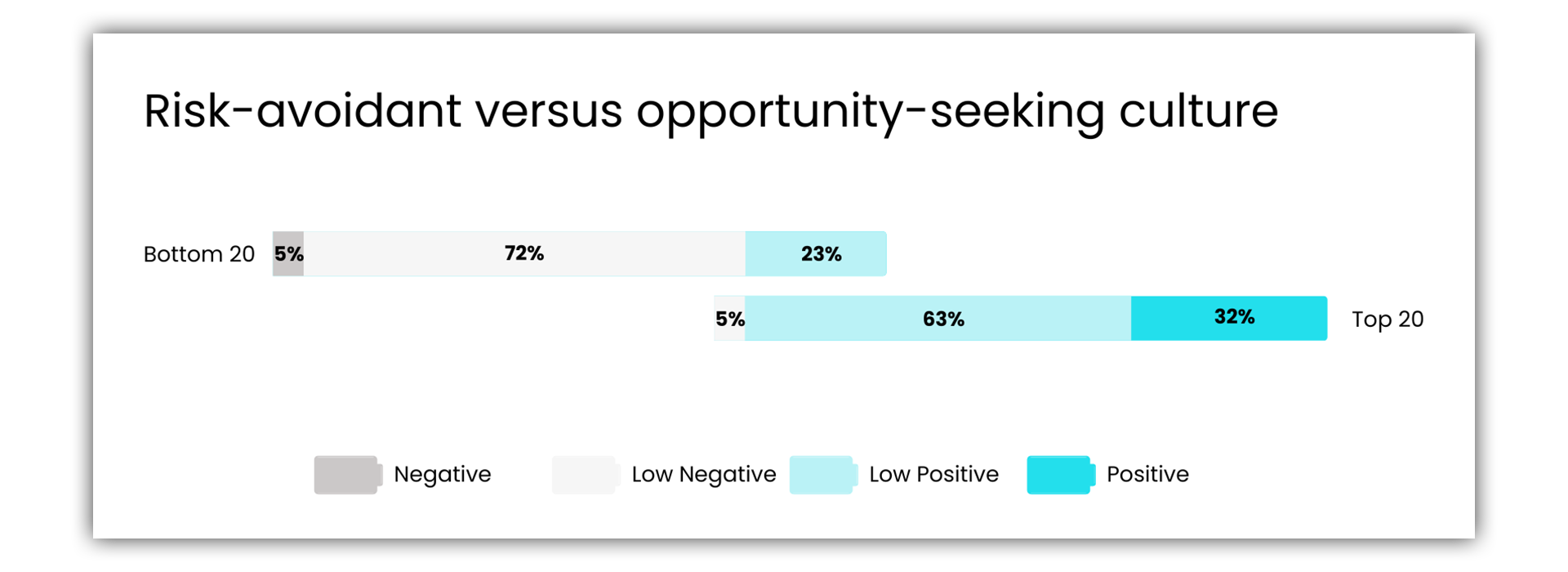

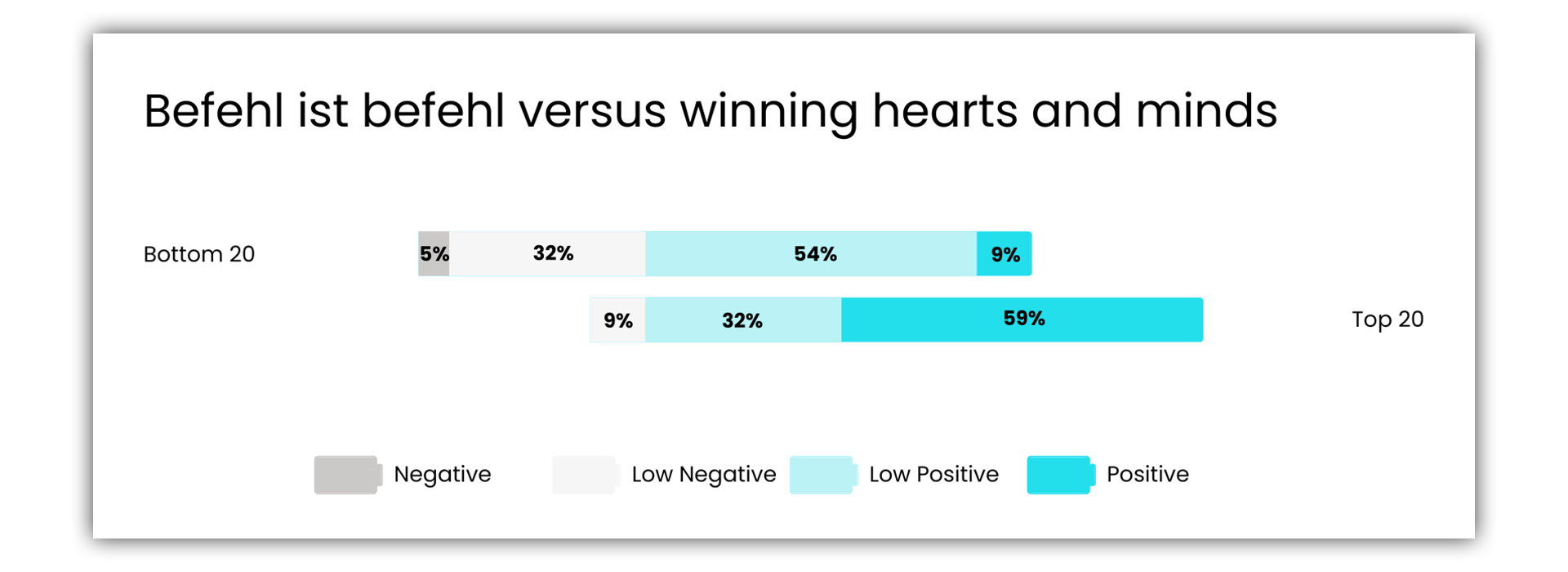

Our data reveals that companies who fail in their change efforts – the bottom 20% in terms of performance – tend to struggle more than others with one or more of the following five destructive behaviour patterns.

- Executives place their personal ambitions above collective goals.

- Distrust pervades among the top team.

- The top team lacks a mandate from major stakeholders to lead change.

- In a culture of risk avoidance, new initiatives are repeatedly rejected.

- Employees are only valued for their performance.

Take a breath. Fortunately, very few organisations embody all five characteristics. Our research reveals that less than 5% of the organisations in our sample score poorly in all these areas. But that doesn’t mean you’re in the clear. Companies that embody 4 out of 5 deadly drainers also tend to have 0 green batteries, which means their chances for a successful change initiative are minimal at best.

What if you’re not part of the ‘nightmare scenario’? In that case, it’s still good to be aware of these ‘evil’ energy drainers and how to recognise them. These behavioural patterns can quickly drain an organization and its resources, leaving them with hardly any energy for change.

1. Executive egos put their personal ambition first

When boardroom executives put individual needs ahead of collective goals, it creates a breeding ground for destructive power battles. This can completely halt any change energy, leaving the organisation paralysed.

“Why should I worry about collective goals,” a manager may ask, “when the top leaders are only looking out for themselves?”

Climbing the corporate ladder sometimes rewards a skillset that primarily requires high degrees of intelligence (IQ). Employees are promoted based on their competence and ability to solve problems in an efficient and effective way. As such, top leaders haven’t necessarily developed the emotional capabilities to lead.

As a result, executives are very content-driven. They sink their teeth into the functional part of the business and neglect the people side. Leaving room for destructive behaviour patterns to fester.

Additionally, their egos might get in the way. Meaning they are incapable of dealing with negative feedback, and tend to take over (read: micro-manage) when the slightest hint of doubt creeps in.

This is all very understandable. But when readying an organisation for change, there is no place for ego-centric executives. The transformation will be painful enough on its own. Effective change leadership requires high degrees of emotional agility. This implies learning to understand your own personality traits but also those of others.

6 signs that egos have hijacked the boardroom:

- Need for control, micromanaging others.

- Fear of diversity: filling the team with ‘clones’.

- Ignoring or avoiding feedback.

- Interrupting others before their point is made.

- Using status to elevate one’s point of view.

- Using the excuse of “no time” to avoid helping others.

If you recognise these signs, you need to start at the top, recharging the Ambitious top team battery. This means that at a minimum, the CEO of the organisation needs to accept individual coaching. Someone who can confront him with his own behaviour and the effect this has on other team members. And helps him develop the ability to deal with negative emotions.

Mandela’s ‘be the change you want to see’ is an absolute must in this context. Consider it a true do or die item before anything else.

2. Distrust among the top team

When there is distrust among the top team, organisational energy will be left on the table as people are more careful about their words and actions.

“Why should I share my inner thoughts and concerns,” an executive might ask, “when I’m unsure how my colleagues will use this information?”

If there are a lot of egos in the boardroom (see drainer 1) it’s unsurprising that the top team doesn’t fully trust each other. Content dominates the agenda and there is little time for teambuilding.

This isn’t as visible as you might think. Top teams who cannot trust each other, are not fighting each other every step of the way. Quite the opposite. Distrust means team members don’t dare to have healthy conflicts. They neglect to discuss how they work together, and what the roles and responsibilities are. As a result, there is no real commitment or accountability of team members.

In soccer, you often see team members scolding each other on the field. Why? They are eager to win and therefore hold their teammates accountable for commitments that they made before the game.

Of course this can escalate too, but if there is no conflict, there are no people who want to win together either.

This is important because your ambitious top team needs to act as role models from the first moment of the change journey. Top executives must demonstrate their commitment, in order to convince the workforce.

So, what is required to build trust among the top team? As cliché as it may sound, going on an offsite goes a long way to start communicating in a different way. But beware; you need to make sure that what happens on the offsite, doesn’t stay there. And whatever agreements you make about how you behave and interact with each other, transfer to the workspace.

As a practical example, you can appoint one person in the team who will check at the end of every meeting: Did we respect the rules of the team charter that we created? Did everyone get in on time? Did we come to a consensus decision? Was the communication in this meeting respectful?

3. No Mandate from Major Stakeholders

When major stakeholders question the credibility of an organisation’s change strategy, any energy generated fizzles in the face of resistance.

“Why should I take all this “Time to Change” nonsense seriously,” a senior employee may ask themselves, “when the union is threatening a strike, shareholders are pulling out, customers hate the new system, and other departments are doing all they can to return to normal?”

Every organisation has a couple of major stakeholders. Those with the power to stop any change initiative in its tracks. These could include financial shareholders, governmental institutions, major customers, or even important employee representatives. If these groups do not see their interests reflected in the changes, you are in danger of losing the support of middle managers.

Why? Implementing change is all about credibility. This is a mix of commitment (are top leaders personally supporting the change and making time for it?), different people repeating the same message (is my department head saying the same thing as the CEO?), and money (are we investing in the solution?).

If the latter is taken away by major stakeholders, this damages the credibility of your transformation.

Is everyone convinced that the status quo needs to change? Do they share a vision for change?

So, what to do? To convince stakeholders, it’s important to spend a considerable amount of time on formulating the need for change and developing a credible change story. What is wrong with the status quo? Why do we need to change NOW?

But an ambitious top team should also generate purpose and enthusiasm for the organisation to change its course. Changing behaviour requires an ambitious change vision. By ambitious, we mean going beyond the ‘simplest’ solution or the fever dream of financial consultants and investors. The aspiring vision should appeal to the broadest possible coalition of stakeholders.

4. ‘No’ is the Norm

When new initiatives meet with repeated rejection from overly risk-averse executives, a vast reservoir of emotional and intellectual energy remains untapped.

“Why should I dedicate so much energy to writing and presenting change initiatives,” a middle manager might argue, “if I know our department head will offer nothing more than mediocre praise and excuses for why he won’t support my initiative?”

When the first three energy drainers are present in an organisation for an extended period of time, it will eventually shape the culture of the organisation. Risk aversion seeps down to all levels of the organisation and ‘no’ becomes the new norm. This will be reflected in a poor score in the Healthy culture battery.

As a result, you will never have bottom-up change. Even more so, you risk becoming an organisation which is poorly connected to its customers. As the people in the field – those who are talking to customers on a daily basis and always know where the market is headed – are unable to get their message across.

Does your organisation have a risk-avoidant culture? Good news: it’s not too late to turn it around, and create a culture of courage and possibilities. To make this shift, you need to reduce hierarchy, increase autonomy and encourage diversity.

This implies finding simple and safe ways to share feedback, turning comments and weaknesses into opportunities and outcomes. It often also includes providing time and setting up arenas for creativity and innovation. Google’s 20% of time that employees can freely use for innovation may be pushing it, but organising frequent Town halls to address open questions or internal fairs to share ideas across all employees are often a good way to start.

Last but not least, bring in different perspectives. From consultants and experts, but also from customers or different employee profiles. Especially success stories from others can help you to challenge long-held beliefs about what is possible and what is not.

5. Disregard for the Emotional Well-being of Employees

When an organisation underestimates the personal effect of change on people, this puts a strain on the energy for change.

“Why should I spread positive words about the restructuring,” an employee may ask, “when my manager fails to understand how it affects me?”

The real reasons why people resist change, often have a personal nature. These are less visible, and easily underestimated. In case of a restructuring, a person’s job might not change, but he will no longer work with the same colleague (social), have direct reports (status), or make decisions on his own (autonomy).

When organisations minimise emotional reactions and ignore the pain that changes can bring, it promotes a culture of denial and creates psychological distance between managers and employees. Hindering teamwork rather than fostering it.

Even if you can’t change the outcome for individual employees, it’s crucial to at least be aware of the personal implications. As management is often accused of “not understanding what the change means for us.” This breeds resistance and drains the Strong connection with employees battery.

Before the big announcement, make sure you’re building a critical mass of employees who know what the changes entail. Together, you will be able to map out which colleagues are impacted by the change, and how.

Crystal-clear communication is critical. Address confusions and uncertainties as soon as possible and as often as necessary. Every communication touchpoint with employees is an opportunity to build trust and intimacy – essentials for energising change. And remember that it’s just as important to articulate what areas will NOT be changing.

Why does no one dare to change things?

If you score poorly on all five of the biggest energy drainers, it’s going to be very hard to start moving the organisation in a new direction. As this means the other Batteries of Change also have low scores.

Few at the table will dare to challenge this status quo. And yet below this timid culture, everybody knows that the current way of working does not work. Change becomes impossible when there is no positive energy.

For a low-energy organisation facing a ‘nightmare scenario’, the possibility of change depends on a genuine willingness and commitment to turn away from business-as-usual:

- For change to be possible, leaders must be convinced rationally that maintaining the status quo is not an option. They need to see and feel the pain.

- For change to be possible, leaders must be willing to let go of their emotional commitment to maintaining the status quo. This also implies that they are open to personal advice and coaching.

When, despite everything, an organisation still clings to the status quo, our advice is quite simple: Get help or get out!

Geert Letens

Research insights and infographics from “The Six Batteries of Change”.