Nut to crack: During a reorganisation, whom do you involve, when and how?

Will my role change? What does the new organisational design look like? What will the impact be on me? Questions like these will be coming at you during a reorganisation. How do you deal with those smartly? Who do you involve? And when do you present what information to whom?

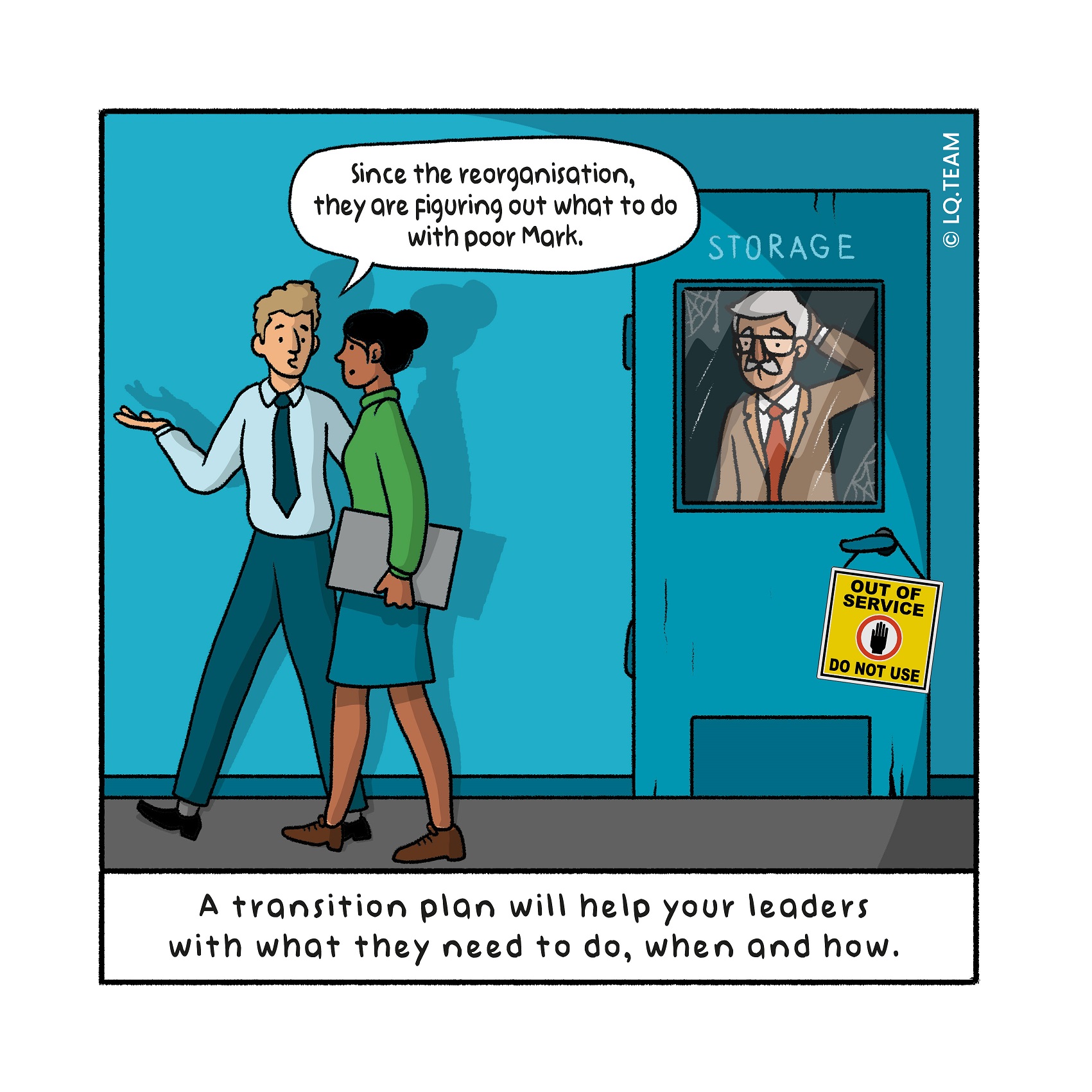

Nutcracker: Transition planning as a vehicle for co-creation with future leaders

A reorganisation is one process that it helps to plot top-down and linearly over time, with clear process steps and milestones. Typically you go through eight steps:

- Definition

- Analysis

- Macro design

- Micro design

- Determining the impact

- Preparation of transition

- Implementation

- Evaluation and optimisation

It helps to go through the steps with a small group, including the critical lea- ders who will eventually give direction in the new organisational structure, as well as with the Works Council, supplemented by one or two of their repre- sentatives, if there is already a good relationship with them. Where necessary, you enhance the knowledge of this group with input from experts.

While going through these steps, you inform the employees and other stake- holders who may be affected by the reorganisation accurately and transpa- rently about the process, which actions will take place, and when.

During step 6, you typically increase the group of people participating. At that point, it helps to involve the managers who will conduct the conversations. You can ask them to prepare a transition plan for their area.

In a transition plan, each leader describes the following:

- Why the organisational structure is changing now

- What success looks like after implementation

- What the design principles of the new design are

- What the new organisational structure looks like

- What the most significant changes are, compared to the old structure

- What the impact of this structure is on different roles

- What the planning of the transition from the current to the desired structure looks likes

- What the enablers are to make the key transition steps, e.g. processes, systems, competencies and behaviour of people

- What risks are involved and how to avoid them

- What the communication flow looks likes

Creating a transition plan means that these leaders experience the content and impact of the new structure and gain insight into what they need to do to make it work. At the same time, it also manages the expectations that certain choices about the organisational structure have already been made. The question that arises is no longer whether this is the proper structure but how to get it to work.

Only when the managers have taken this step and transition plans are clear, and approval has been obtained from the Works Council (when required), can you communicate to the group of employees subject to the reorganisation. Typically you would first communicate the why, the intended result, and the main consequences in full. Straight after, one-on-one conversations usually occur with every employee who has experienced uncertainty.

Unfortunately, this uncertainty cannot be avoided, but you can diminish the length of uncertainty by quickly, but thoroughly, going through the steps in a “pressure cooker” form. I have seen projects of six to eight weeks for organi- sations with over a thousand employees, which have been successful.

The next example illustrates how you approach the above in practice.

Real-life example: Patience remains a virtue

A logistics director leads a reorganisation. The new organisational structure is known. The director hesitates. Does he give in to requests to provide information about the new organisational setup to employees who know they will be affected now, or does he wait until more details are known about the implementation?

He decides to wait. He only communicates widely about the process, not about the content. He gives the department managers the details a week in advance, having them sign for secrecy. He asks them to write a transition plan. In it, they describe the conse quences of the new structure for each function, how the transition from the old to the new structure will take place, which preconditions apply and in what phases it will be implemented. This also gives the director additional insights. It becomes clear to him, for example, that some structural choices can only become effective in a year because they are related to the conversion of a system. This was previously not visible.

After this process step, the managers know what to say to employees contentwise. To enable managers to feel comfortable having the conversations, they practise the one onone conversations, simulating discussions about problematic issues, and formulating answers on challenging questions.

Individual letters are ready, and now clarity can be provided to “the general public”. The director announces the new organisational structure. Immediately after the announce ment, on the same day, individual conversations with employees occur, conducted by the department managers and their hr business partners.

Afterwards, the logistics director asks for feedback from employees about the process. It’s pretty consistent. Not all of them are happy with the outcome, as expected. But overall, they are positive about department managers’ wellprepared conversations and clarity. This has given them the confidence that a careful process has been followed – a big compliment to the team.

Tip for change leader

Every organisational structure is flawed. In explaining a new organisation structure, therefore, put at least as much emphasis on what you intend to achieve with the revised structure: acceleration of decisionmaking, stimulation of new collaborative relation ships, and enhanced focus on the customer. Invite people to think about how they can contribute to achieving these goals by working in the new structure.

Tip for change enabler

Include a step in the organisational design plan in which the intended structure is tested against reallife examples before being finally approved. How would decisionmaking transpire? Does this solve current pain points? Will this indeed lead to acceleration? Is the customer more central? By doing that test, you can check whether the design is solid or whether adjustments are still necessary.

Kernel: Timing is critical

Make the process of organisational design crystal clear and communicate it extensively. Only share the content of the approved organisational design with a broader audience once line managers have their transition plans ready and they feel prepared for the conversations they are about to have.